Puertas correderas francesas de doble bolsillo de 48 x 96 pulgadas de vidrio transparente | Lucia 2166 seda blanca | Kit de accesorios para rieles | Interior de madera maciza puertas resistentes para dormitorio : Herramientas y Mejoras del ... - Amazon.com

Amazon.com: Persianas verticales para puertas corredizas, 90 pulgadas de ancho x 84 pulgadas de largo, hechas a pedido con filtro de luz de hierba tejida con protección UV para patio, divisor de

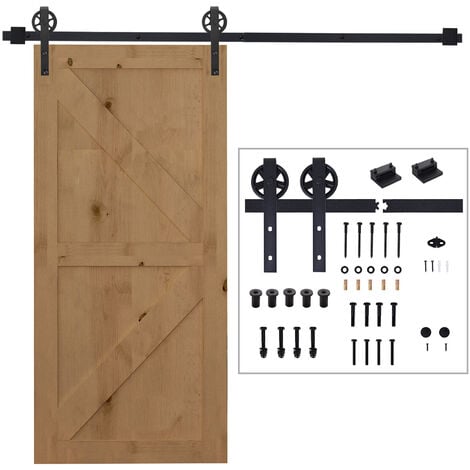

Amazon.com: Homacer Kit de herrajes para puertas corredizas de granero de triple riel rústico negro, tres rieles planos de 12 pies de largo, para puertas interiores de tres o triples (para grosor

Amazon.com: Puertas correderas de vidrio triple granero de 8 pies de altura con raíles de 14 pies | Planum 2102 vidrio templado esmerilado | juego de deslizador de riel de montaje superior

CCJH 274CM/9FT Herraje para Puerta Corredera Acero Inoxidable Kit de Accesorios, Guia Riel Puertas Correderas, Forma T Puerta doble : Amazon.es: Bricolaje y herramientas

Amazon.com: Puertas corredizas de 36 x 80 con herrajes | Lucia 31 blanco mate | Robustos carriles de montaje superior molduras juego de accesorios | Despensa cocina 3 paneles puertas de armario

Amazon.com: Puertas correderas de vidrio triple granero de 8 pies de altura con raíles de 14 pies | Planum 2102 vidrio templado esmerilado | juego de deslizador de riel de montaje superior

Amazon.com: Homacer Kit de herrajes para puertas corredizas de granero de triple riel rústico negro, tres rieles planos de 12 pies de largo, para puertas interiores de tres o triples (para grosor

Amazon.com: CHICOLOGY Persianas de puerta corrediza, persianas para puertas corredizas de vidrio, persianas de puerta corrediza de vidrio, persianas verticales para puertas de patio, divisor de habitación, marrón skyrise (filtro de luz)

Puertas corredizas de 36 x 80 con herrajes | Lucia 31 blanco mate | Robustos carriles de montaje superior molduras juego de accesorios | Despensa cocina 3 paneles puertas de armario de madera maciza para dormitorio : Herramientas y ... - Amazon.com

Amazon.com: Puertas correderas de triple granero marrón de 96 x 96 pulgadas con rieles de 14 pies | Planum 2102 Ceniza de jengibre | Juego deslizante de rieles de montaje superior pesado

Amazon.com: Puertas correderas francesas de doble bolsillo de 48 x 96 pulgadas de vidrio transparente | Lucia 2166 seda blanca | Kit de accesorios para rieles | Interior de madera maciza puertas

Puertas corredizas de 36 x 80 con herrajes | Lucia 31 blanco mate | Robustos carriles de montaje superior molduras juego de accesorios | Despensa cocina 3 paneles puertas de armario de madera maciza para dormitorio : Herramientas y ... - Amazon.com

Amazon.com: Puertas corredizas de 36 x 80 con herrajes | Lucia 31 blanco mate | Robustos carriles de montaje superior molduras juego de accesorios | Despensa cocina 3 paneles puertas de armario

Amazon.com: Cortinas de patio con decoración floral para puerta corredera, cortinas opacas multicolor para dormitorio con ojales, cortinas para ventana para sala de estar de 42 x 63 pulgadas de ancho :

Amazon.com: Puertas correderas de vidrio triple granero de 8 pies de altura con raíles de 14 pies | Planum 2102 vidrio templado esmerilado | juego de deslizador de riel de montaje superior

Amazon.com: Puerta corredera de vidrio transparente de 3 litros, 56 x 96 pulgadas, Lucia 2555 blanco mate, montaje superior resistente, juego de rieles de 6.6 pies, puertas de armario de madera maciza