Amazon.com: Yfigo - Anillo de serpiente con diseño de animales punk, vintage, para hombres y mujeres, aleación, Adjustable, Negro, CD40-black : Ropa, Zapatos y Joyería

Amazon.com: Anillo de serpiente de acero inoxidable para hombre y mujer, color amarillo o blanco, anillo de serpiente, anillo de hombre, acero inoxidable, 7, Blanco : Ropa, Zapatos y Joyería

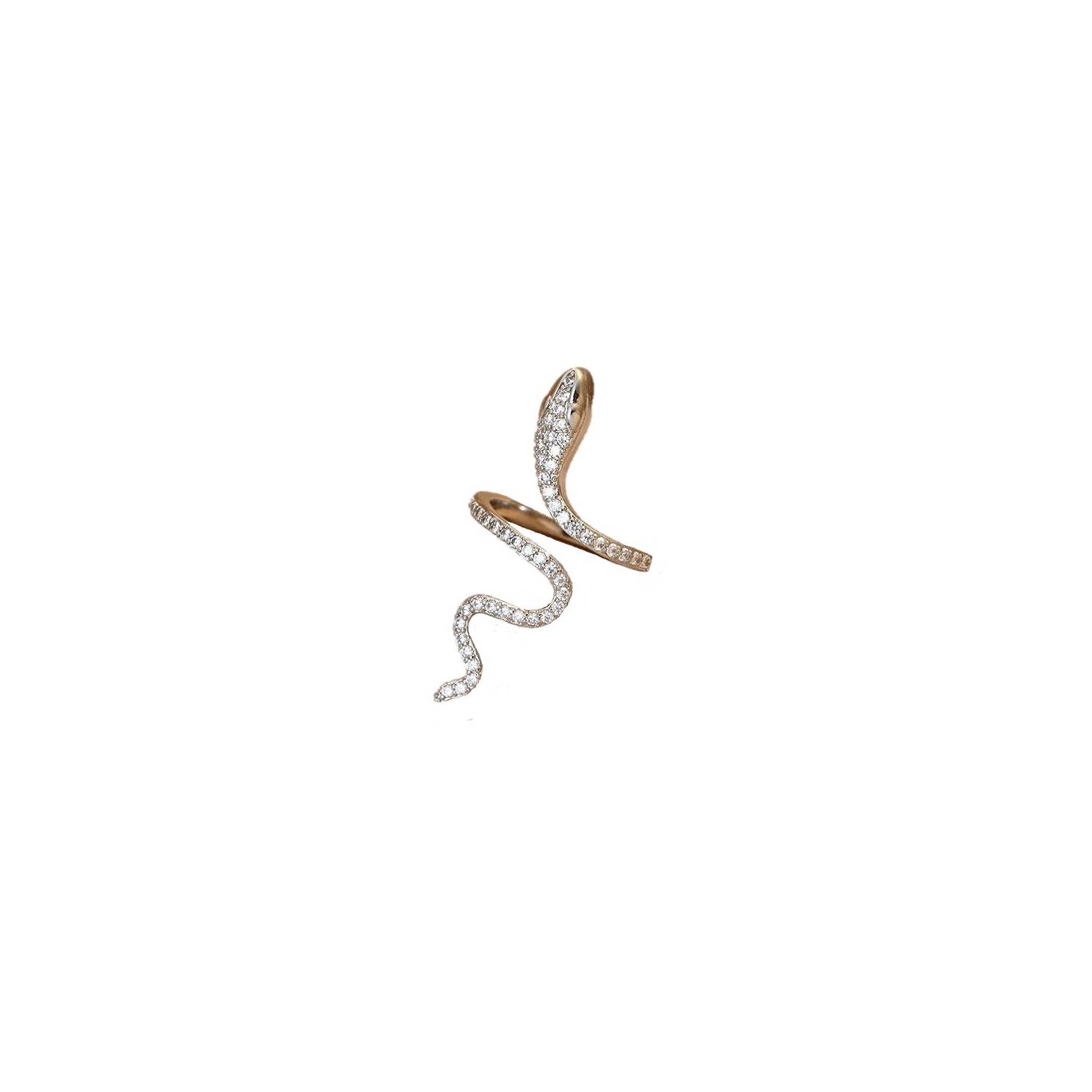

Amazon.com: Anillos de serpiente para hombre, anillo redondo de diamantes de gran forma con piedras preciosas y diamantes de imitación, anillo azul zafiro, anillo vintage de pavo real, anillo grande (A, talla

Amazon.com: sovesi Anillo de serpiente de oro para hombres y mujeres, anillo de serpiente de plata gótica, ajustable, anillo vintage para hombres Eboy, Metal, Alto pulido : Ropa, Zapatos y Joyería

anillo de serpiente de plata de ley para hombre, anillo de plata de ley , estilo gótico | Shopee México